I have Wee Cankles

I was born with a hereditary neuro-muscular disease called Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (CMT), pronounced (shark-o mah-ree tooth).

The name is unimportant in terms of understanding the disease. It is named for the 3 Doctors who first described and wrote about it in the 1800’s, Dr Jean-Martin Charcot, Dr. Pierre Marie, and Dr Howard Henry Tooth.

When I was a kid, my parents didn’t use the phrase “Charcot-Marie-Tooth” to describe my condition. Why would you? It’s a weird name. I would hear it mentioned at Dr’s appointments and I’d wonder what sharks and teeth had to do with my feet. We described my condition to others as weak ankles. Only, my little child’s brain didn’t hear “weak ankles” it heard “Wee Cankles”. So, in my mind, I had a disease called Wee Cankles! One day it clicked as “weak ankles” and I was like, “Oh, yeah. That makes sense”! The word mash-up “cankles” as a description of people who have ankles the same size of their calves (usually when the ankles are on the fatter side) wasn’t in my vocabulary then. But, with the wasting I have in my calves now causing very little definition between skinny calves and skinny ankles, I do have wee cankles!

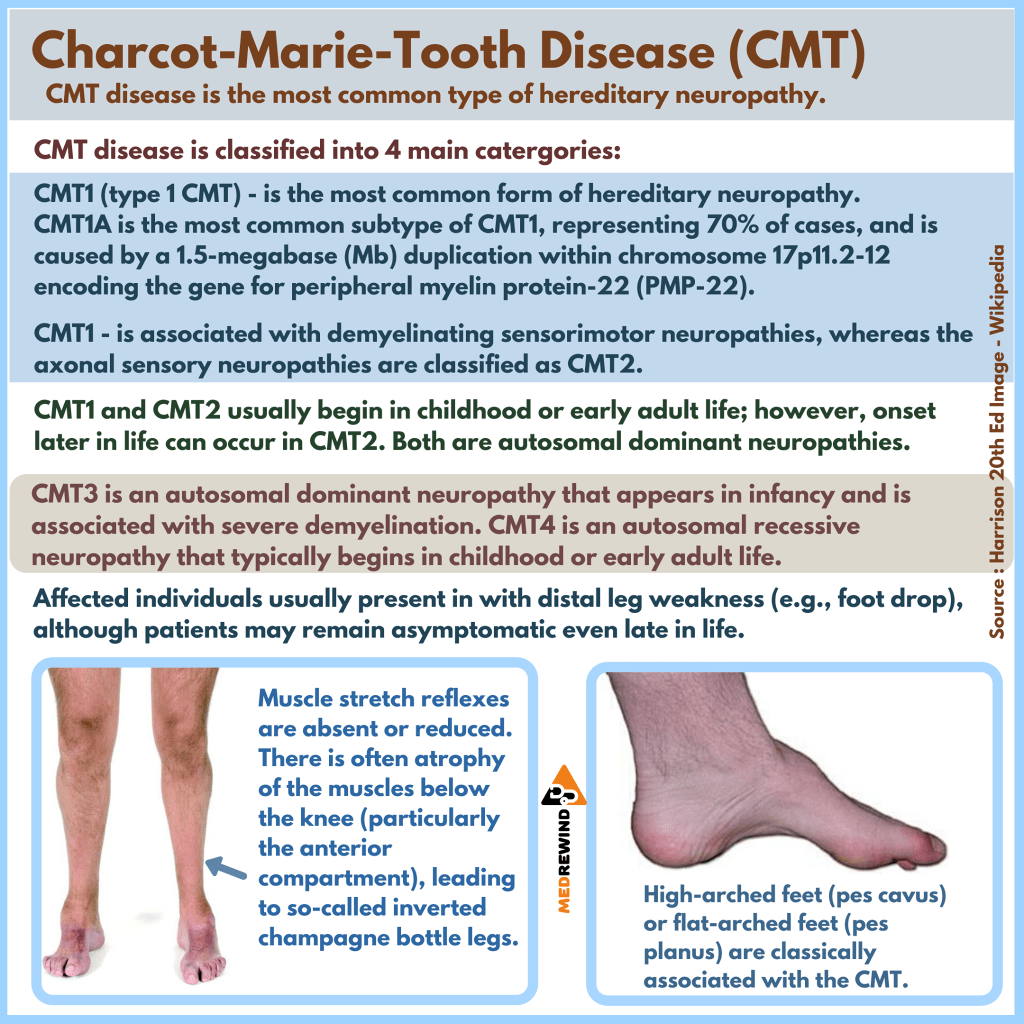

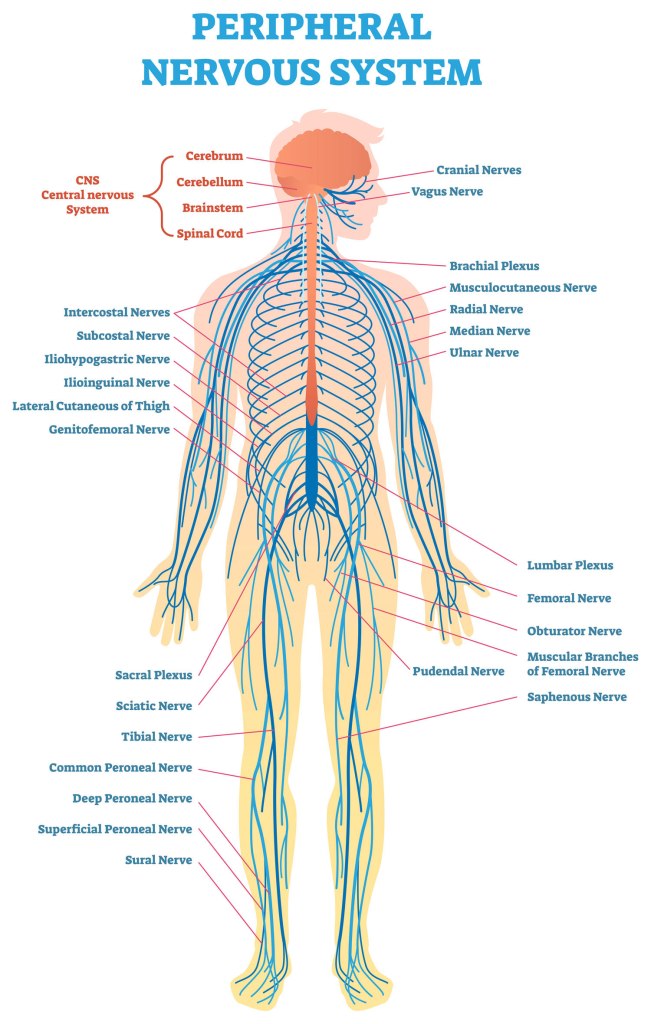

CMT consists of a group of similar diseases characterised by gene mutations which cause damage to the peripheral nervous system. The damage occurs either to the myelin (the nerve covering) or the axon (the inner core of the nerve). This damage interferes with the brain’s signals to the muscles and results in motor and sensory issues of weaker and delayed reactions and sensations.

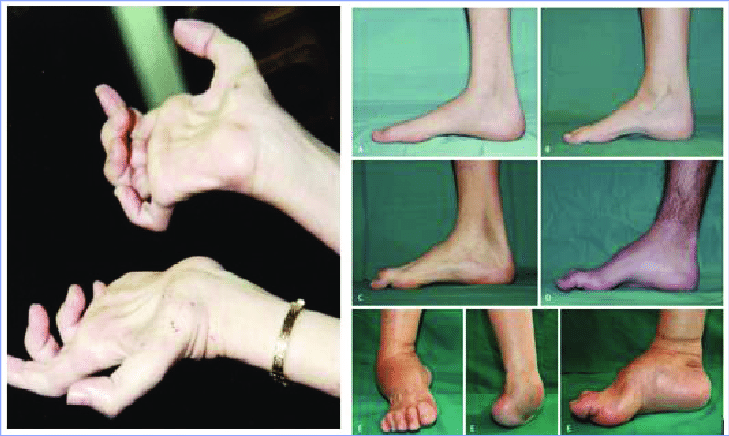

The more common symptoms of the disease include muscle weakness, decreased muscle size, decreased sensation, hammer toes and high arches. Hand function is also usually affected resulting in poor fine motor skills and finger strength impacting the ability to do things such as holding a pen, doing up buttons and zips, and tying laces.

I can’t tell exactly where my limbs are so I sometimes get a little close to things like doorways, walls, table legs, the ground. As a result, I watch my feet when I walk (not ahead of me), and I look at my fingers when I type (not the screen). I don’t drive because I can’t feel my feet on the pedals and need to look at them to change pedals and to confirm that they are in fact still on the pedals – obviously, this is dangerous, so I don’t drive. I had my learner’s licence when I was 19 and got some driving lessons. There was an incident where I went straight over a roundabout rather than the more traditional round the round about. My brain and muscles couldn’t coordinate slowing down, braking, and turning the steering the wheel so it all just kind of froze and over we went. Thankfully it was a roundabout with a low profile so there was no damage and the instructor was already wearing brown pants so his dignity was preserved.

I was diagnosed at an early age which is somewhat unusual. CMT is a rare disorder with 1 in 2500 being affected GP’s don’t see it a lot. I initially thought 1 in 2500 didn’t sound rare but when I applied the statistic to larger populations, I got a better sense of the numbers. For example, when applied to the population of the USA (328 million people) the number affected with CMT, based on 1 in 2500, is 132 000. Applied to Australia’s population of 25 million the number of people affected is 10 000 and out of the entire world’s population of 7.6 billion, the estimated number of people with CMT is 3 million and forty thousand. 3 million and forty thousand is a very big number but as this Tik Tok video created by Humphrey Yang (https://www.tiktok.com/@humphreytalks/video/6798276393634467077) shows, there is a HUGE difference between 1 million and 1 billion. And then there is the medical definition of rare. In the USA, a disease is classified as rare if it affects less than 200 000 people (https://www.genome.gov/FAQ/Rare-Diseases#:~:text=A%20rare%20disease%20is%20generally,million%20to%2030%20million%20Americans) and in Australia the classification for a rare disease is if it affects less than 5 in 10 000 (https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/chronic-conditions/what-were-doing-about-chronic-conditions/what-were-doing-about-rare-diseases). So, it fits the criteria of rare! I did the maths!

Despite being rare, it is the most common form of inherited neuropathy.

Growing up, very few doctors had heard about it, and I usually had to educate them about the disease. More doctors are aware of it these days, but people still struggle to get diagnosed due to a lack of knowledge of the disease or a lack of understanding of how it affects people. Some of the mutations in various CMT types have been discovered and can be diagnosed through a blood test but there are plenty which have no test and rely on an elimination diagnosis of ruling out other diseases.

The various types of CMT are generally distinguished by age of onset, inheritance patterns, severity and whether the defect is found in the nerve axon or myelin. And it affects everyone differently. Some people can have it but not have any symptoms till late in life, some never show symptoms despite having the disease. There is one kind of CMT that is x-linked where people can be carriers of the gene and able to pass it on, but they don’t actually have the disease. However, this is not the case for most types of CMT where if you have the gene, you have the disease with the potential to display symptoms.

Within my own family there are 3 people who have a confirmed diagnosis of CMT1a (the most common type) and while we share some commonalities, we also experience vastly differing symptoms. My Dad was diagnosed at the same time that I was. He had gone through life spraining his ankles and always being just a bit slower physically than his peers. However, in his youth he played rugby, rode horses, and played polo and at nearly 70, he is still active, drives a car, gardens and does yoga.

Because CMT predominantly affects hands and feet and the impact on walking is more apparent and visible than other symptoms, the focus of treatments and interventions centres on these areas. This has resulted in a misunderstanding of the wider impacts of the disease. As shown here https://www.cmtausa.org/understanding-cmt/what-is-cmt/ CMT has a greater affect on the individual than just hands and feet. Conversations in CMT Facebook groups support this.

There are frequent discussions within CMT Facebook groups of optic and aural nerve deterioration, tinnitus, neurogenic bladders, impaired bowel functioning and swallowing and breathing issues. As CMT is a disease of the peripheral nerves, it makes sense that all muscles serviced by peripheral nerves would be affected, not just hands, arms, legs and feet.

A few years ago, I had my gall bladder removed due to gall stones . I had not been experiencing anywhere near the level of pain associated with gall stones that other family members had (It’s a family thing – yay, genetics). The stones were discovered when looking for something else relating to a slow digestive system. The surgeon who removed the stones said that my lack of pain was likely due to CMT nerve damage. This was the first time I was made aware that the sensory damage could also be internal and present in areas other than my limbs.

CMT is degenerative and, as a result of the nerve impairment, muscles malfunction, and over time weaken and waste away.

For some the deterioration is quick. For others, it is slow. Some people experience a dramatic loss of function over 12 months which sees them go from a fully functioning, average abled person to being considerably disabled.

For me, my deteriorations have always been gradual. For instance, it took me about 2 years to realise that my hands were getting worse. I’ve always worked in call centres which generally requires a lot of accurate typing. Attention to detail and proof reading had kept me just close enough to KPI’s to maintain employment but I started noticing that I was making more errors including missing letters within words.

I realised that my fingers had become too weak to press down the keys in my normal “fast” (fast for me!) typing style. I was hitting some keys alright but other keys were being missed. I changed my typing style, going slower and focussing my attention on each key stroke. My accuracy improved but my speed went down. The extra effort I was exerting to press the keys lead to pain and discomfort from fatigue and overuse.

I got a soft touch keyboard and voice dictation software which meant that for the most part, I don’t have to type, I can just speak into a microphone. But if I do have to type, the soft touch keyboard makes it easier.

One particularly frustrating thing that was happening during this time was where I’d write a great swathe of info in call notes and then look up from the keyboard to see that it had disappeared, and I had to write it all again.

It was so aggravating. I had no idea what was happening, but I knew it was something to do with my wayward fingers. Because of my finger weakness, I am a two-finger typist. And finger muscle contractures cause me to type with curved index fingers. This exaggerated curve on the left hand was causing me to hit the “alt” key with the palm of the hand at the base of my index finger and then when I hit a certain key with my fingertip it activated a shortcut that deleted all the text I had written. (I have an amazing ability to do odd things accidentally but which I can never replicate intentionally). My solution to that was to remove the “alt” key covering.

It was also around this time that I started struggling to hold a pen. I’ve never held a pen “correctly”. The teachers in my early school years tried to change how I gripped my pen, but I couldn’t use it like that. I didn’t have the strength in the areas required to hold a pen “correctly”. I’ve always had a modified pen grip but that started slipping. So, I had to work out a new way to hold a pen.

I now hold a pen by resting it between my thumb and index finger and gripping it between my index and middle fingers. I have to hold it tight, or I lose my grip so writing for any extended period (more than a minute) is very tiring.

I deal with the impacts of this disease with humour and self-compassion. When I’m having a “bad leg day”, or realising that I’ve lost a bit more ability, I allow myself to be sad and take things easy. Maybe take a day or two to grieve the loss. But I always say that it’s a short wallow in self pity and not a destination. You can visit but you can’t unpack and stay. Letting myself feel the sorrow means I acknowledge it, I name it, I come to terms with it, and I pick myself up again and find a new way to do things. A while ago, I had the realisation that I had 2 options: to give up and say it’s all too hard, or to push on and make the best of the situation. Giving up wasn’t a valid option so essentially there was only one option: to keep on keeping on. You get one life and wishing things were different doesn’t change things. You play the hand your dealt.

Humour is a great release for me in dealing with life and its challenges. To be able to see the light side of things, and have a laugh at myself. For instance, I sometimes have very mild spasms where a muscle just does what it wants. I was at a market stall and picked up a leaflet to read. My hand chose that moment to have a little twitch. So, I essentially picked up the piece of paper and immediately threw it on the ground with a flick of the wrist. Much to my own and the stall holder’s surprise. I had to explain to the stall holder between fits of giggles, what had happened and that I hadn’t chosen to pick up the leaflet simply to throw it on the ground.

In this post, I have outlined what CMT is, how it affects the body and some of the negative aspects of its impact on me. I do not intend this blog to be a pity party and in future posts I will be talking about the things I can do (such as building an amazing garden), and the positives that CMT has brought to my life (strength, determination, resilience, compassion, empathy). I will also not be focussing solely on my CMT. I intend to discuss mental health as well as general musings about life.

Till next time…

References:

https://www.mda.org/disease/charcot-marie-tooth/types/cmtx https://www1.rarediseasesnetwork.org/cms/inc/Charcot-Marie-Tooth/What-is-CMThttps://www.facebook.com/medrewind/photos/a.943583099050740/2912371532171877/?type=3 https://www.epainassist.com/nerves/what-happens-to-untreated-charcot-marie-tooth

The Role of Mutations in Genes PMP22, MPZ, LITAF, EGR2, NEFL, MFN2, KIF1B, RAB7A, LMNA, TRPV4, BSCL2, GARS, HSPB1, GDAP1, HSPB8, DNM2, PRX, MTMR2, SH3TC2, SBF2, NDRG1, FGD4, FIG4, YARS, GJB1, PRPS1, in Charcot-Marie-Tooth Syndrome – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Overview-of-Skeletal-Disorders-in-the-Legs-and-Hands-of-Patients-with-Charcot-Marie-Tooth_fig4_339325328 [accessed 25 Jul, 2021]